Strategic uses of geographic mapping in UK movements

As part of our work building Mapped as a visual mapping tool for movement-building, we wanted to develop a deeper awareness and conceptual clarity around the theme of mapping. We know that mapping is important because it grounds organising in a place. This grounding in place—including workplace—is perhaps what distinguishes organising from other approaches to social change.

To that end, we commissioned Natasha Adams to conduct some research into how movements in the UK are already using geographic mapping practices strategically, and how they might use them more effectively in future. Natasha is a brilliant movement researcher and strategist who has done several project mapping the ecologies of social movements, such as the climate , migrant justice and women’s movements .

Alongside a short literature review, Natasha interviewed twelve organisers from the climate, worker, and migrant justice movements, as well as Everin and Jan from our team. Our goal was to understand how UK organisers are currently using maps, reflect on how to use them more effectively, and identify what tools are currently missing, in order to inform the ongoing development of Mapped.

We see this research as a starting point of a wider research project intended to popularise, enrich and evolve the mapping methodologies used by organisers. This initial research began with geographic mapping only, but eventually we would like to explore polysemic notion of maps in movements, including power maps, network maps and more. We are also interested in engaging more deeply with radical critiques of mapping, including but not limited to decolonial perspectives, in order to reflect how a mapping tool like Mapped could be used to undermine, rather than reproduce, domination and exploitation, and to build alternative power structures.

You can read a summary of the research findings below or download the full paper here .

The power of mapping

This research revealed that mapping is already playing a key role within movement organising, but its transformative potential remains largely unrealised. All interviewees were using geographic mapping to further their work for social justice, in myriad ways dictated by their strategy and focus, often intersecting with relational and power mapping. It is clear that geographic mapping is a critical tool to win campaigns, build power and affect social change.

However, there are many things that organisers would like to map that they are not currently able to. Considerable impact could be unlocked through supporting movement organisations to collect and aggregate the data that would help them win campaigns, and to provide routes for them to map this geographically in relation to supporters, decision makers, communities and other strategic place based insights.

Some considerations

The map is not the territory

Maps are not neutral representations of space — they are political artefacts. Traditional cartography has long served colonial and capitalist interests, demarcating ownership, guiding extraction, and defining what is seen as valuable or visible.

“Maps articulate statements that are shaped by social relations, discourses and practices, but these statements also influence them in turn. Hence, maps (and atlases) are always political.”

As one interviewee put it: “Mapping is a tool of colonialism, of capitalism. Google Maps is not objective."

When movements use corporate mapping platforms, they also inherit their biases. Recognising this context opens the door to alternative, participatory forms of mapping — what some call counter-cartography — that help communities represent themselves, define their own territories, and visualise power differently.

Collecting data

The sophistication of mapping practices was closely tied to how groups collect, structure and maintain data. Interviewees used a mix of tools — Action Network, Airtable, Mailchimp, spreadsheets, and sometimes even paper records. The key lesson here was that mapping starts with data, not visualisation. Without good collection and maintenance practices, mapping quickly breaks down.

Online to offline organising

One interviewee spoke about the importance of having "tools that can go online to offline and back." For example, sheets that could be printed out to collect information on paper in the right format to manually input into spreadsheets afterwards. This means data can be quickly collected from large numbers of members or supporters and fed into spreadsheets and strategy.

“We used a visual of a paper map of the UK with sticky notes — showing where we can mobilise, showing our power.”

“We do on paper power mapping, looking at who needs to move… then we overlay information on a spreadsheet — opportunities to take action, political context, identifying opportunities for action… Corporate targeting, mapping network relations and connections, making clusters of visual information.”

Some interviewees worked more offline, or more online, but well over half had at least some success in bringing people from email lists, e-actions and social media into real life activities, from attending events to leading actions. These activities were reported as most successful when bringing people into relationships with others in their area passionate about and/or affected by the same issues, especially where there were already active groups or at least a couple of deeply engaged people. Getting people organised in communities sits at the intersection of geographic, relationship and power building.

“Our power mapping starts small and geographical, builds up around issues. There is synergy and tension between geography and where people are at.”

The role of mapping in social change strategy

The following use cases demonstrate the most significant findings from the research that demonstrate how geographic mapping can serve social change strategy.

Fostering connections and building power

Using maps can be key to building people-power. By mapping your base, you can identify areas of strength and weakness and direct strategy accordingly. For example, by mobilising those already engaged in areas of strength, or organising to recruit more leaders in areas of weakness. You can identify where best to host events and actions, connect people, groups and organisations to each other and enable them to see where actors are located they may want to connect with.

Good use of geographic mapping can facilitate deepening of engagement from online email lists or social media to real world connections and action. Mapping can show up where geographically there may be unlikely alliances — between local communities and climate activists opposing polluting infrastructure for example, or between faith groups, unions and anti-poverty campaigners all concerned about issues in an area which share root causes.

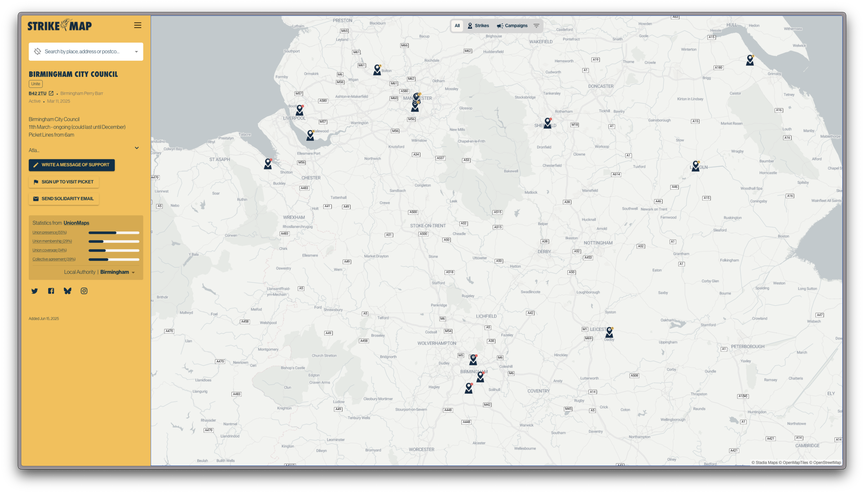

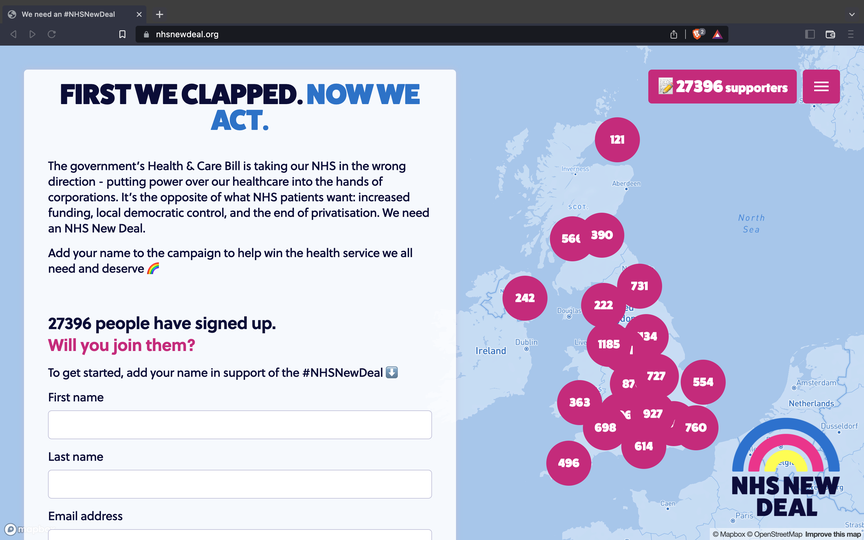

Targeting decision makers and demonstrating power

All levels of democratic decision making are constituency based in the UK, from local councillors to directly elected mayors, MPs and so on. These decision makers can be influenced by their constituency. Mapping can therefore be powerful when it enables connection of people to their decision makers, and when groups or organisations can show breadth of public support for their cause in a particular constituency or area. Although not so democratic, other local bodies can also be influenced through local pressure, from businesses to NHS Trusts, especially when significant public support is demonstrated. Social proof through a map, showing a campaign taking off and the strength of feeling through actions, events and supporters can be very powerful.

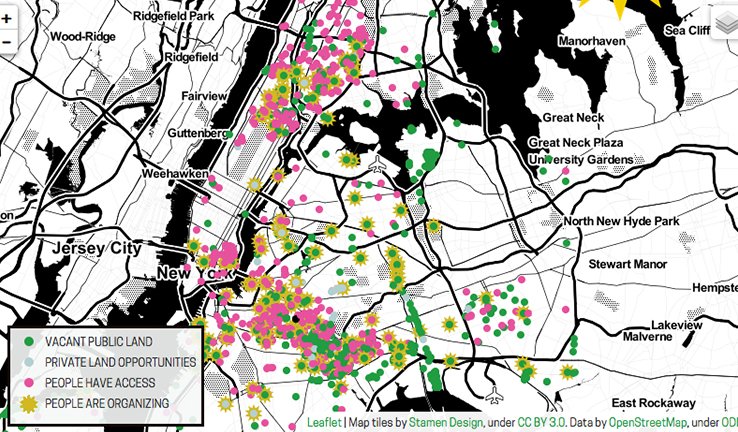

Crowd sourcing data & leveraging accountability

Maps can also serve as a powerful way to crowdsource data — from inviting uploads giving details about local groups to land use, reporting police harassment, bribes and corruption, there are almost endless possibilities. Where injustices are mapped and tracked, these can be made visible, along with those responsible, and accountability can be sought on a wider scale in a way more likely to attract widespread public support. Interactive maps can be a fantastic way to conduct crowd sourced research with quantitative and qualitative data, including the gathering of stories and personal testimony, to generate bodies of evidence in support of your cause.

Using data strategically

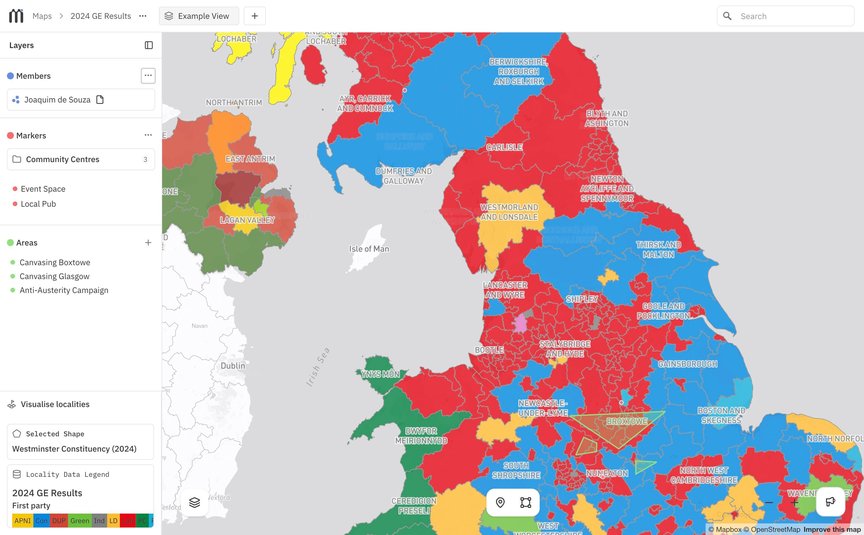

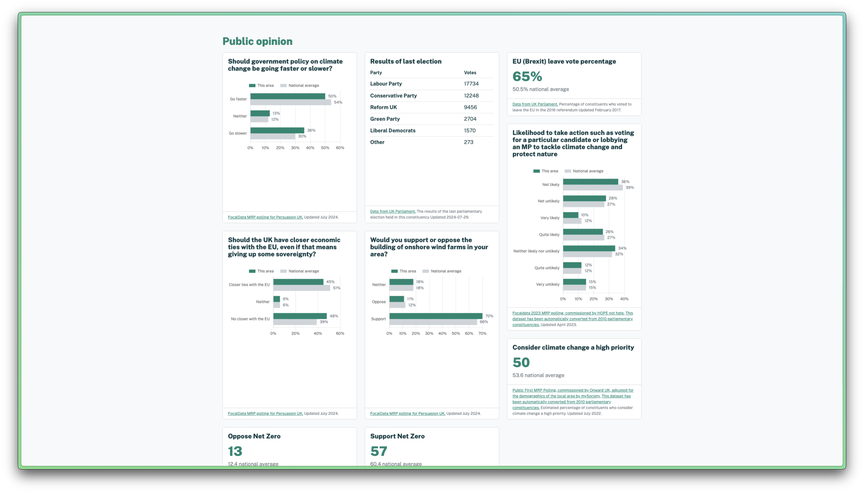

The relationships between things can be identified when layers of data are combined in reference to geographic location. Matching supporters to groups they may ally with, meeting places and events, and to decision makers of all kinds have already been mentioned above. As shown in the picture below of the Local Intelligence Hub’s data layering options, such data can be combined with all manner of other data sets, for example utilising the most recent public opinion polling and Government statistics. This can help to see where the public support, oppose or sit on the fence in relation to your issue, to target organising, media and communications work, and so on.

Reclaiming and redefining spaces

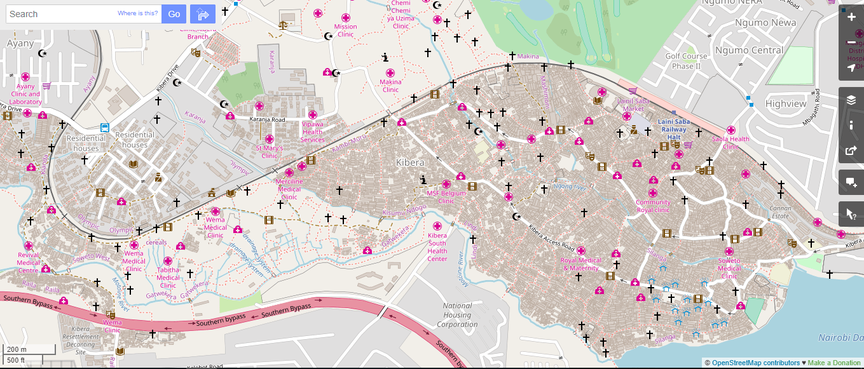

When maps are made through counter cartography, they can map for the first time places that are not served by commercial mapping (such as the project mapping the Kiberia slum in Nairobi), redefine boundaries, enable squatting, repurposing and reclamation of land. Such mapping can empower people to completely rethink what is of most importance in their area and their relationship to the land, terrain, people and organisations found there.

Dream mapping functionalities

Connecting up relevant local groups, events and organisations

Two thirds of interviewees wanted to connect their supporters to relevant local groups, organisations, and or events, to help build and strengthen the wider movements they are part of.

“The biggest thing I want to be able to do… Imagine you’re a random person, you want to know ‘what is happening in my area?’ – seeing groups, where they meet, events they could get involved with.”

But people were also quick to raise some significant issues with this, including:

- Concerns around safety – 50% of the groups campaigning on migration and race were concerned about far right targeting of staff and communities if they were to share locations.

- Maps often don’t show the knowledge movement actors need – there are some things you can only understand by speaking to people involved in a group or in a community. The things websites and publicly available data share are not necessarily the things social movement actors would like to map and understand – so this kind of mapping can only supplement, not replace, relationship building and real conversations.

- Doing this relies on a culture of sharing – but although some organisations are happy to share events and groups and link up as much as possible, bigger NGOs especially have a track record of ‘hoarding’ data rather than sharing, although many staff inside them would prefer to share.

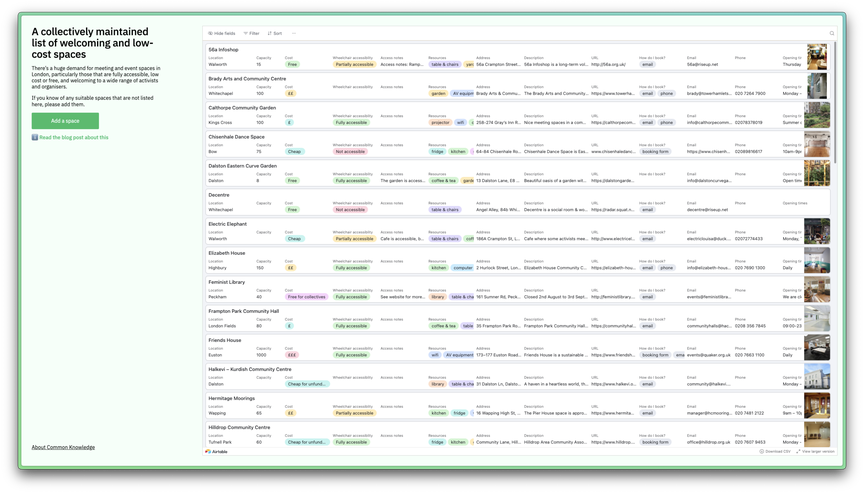

Identifying community meeting spaces

Over 40% of interviewees were interested in using maps to identify these, to find places to suggest for meetings and events to build deeper relationships with supporters, make new connections, provide political education on issues and spur people into action. But as above, it would be hard to get the nuance of information that could come from personal local connections and conversations in such data sets. Meeting places that seem central might look good, but be poorly used by people interested in action on a particular issue.

Plotting supporter density on a visual map

Although lots of interviewees were already plotting their own supporter density on maps, sometimes this was only done in crude ways that could be improved (e.g. through better data, like postcode) and a third said this was functionality they’d love to have and don’t already.

Gathering other geographic data sets to layer onto maps

A quarter of interviewees said they would be interested in the capacity to pull together niche / bespoke data sets to layer them on maps, with supporter density or other relevant data.

“Being able to make requests would be helpful – e.g. The Movement Research Unit has a network of people that can respond. Movement infrastructure like that would be helpful to respond to each use case and develop data for different targets.”

Key reflections

Here are some reflections and practical recommendations drawn from the research — aimed at organisers, infrastructure providers, funders and technologists working at the intersection of mapping and movement strategy.

-

The connective tissue of movements is missing

People want to build solidarity, connection and power with other local people, groups and organisations. There is currently no consistent infrastructure to do this. It’s a big gap that needs addressing to meaningfully counter the rise of the far right, to support communities to stand in solidarity and protect each other in the face of this threat, and to build an emergent alternative.

-

Consider map-making as an organising process

Maps are not neutral — they reflect the priorities and views of the map maker. Creating maps in collaboration helps clarify what’s important to your community and what your collective understanding of power looks like.

-

Mapping begins with strategy

Geographic mapping is not generally useful in and of itself — it's what you use it for, how it fits your strategy, that will be important. There are many powerful ways it can be used which won’t be relevant for

your

campaign. It’s important to start with what you want to achieve and to make plans backwards from there, determining what you think is needed to achieve each necessary step in pursuit of your goal.

-

Collect better data

Gathering more granular information (like postcodes) enables more detailed analysis. The better your system and process for storing and managing this data, the easier it will be to use it strategically. For example, being able to log actions taken, individual relationships, conversations or trainings attended by members could be particularly useful for organisers to deepen their relationships with their members and use their time strategically.

-

Protect people’s personal data

In the context of shrinking civic space and increasing surveillance, harassment and imprisonment of activists in the UK, it’s very important to think about online safety and potential surveillance. Think twice before uploading data to commercial tools or using unencrypted chat. Always protect sensitive information about your members.

-

Layer meaningful data

The data that will best serve your needs will vary according to your strategy and focus. Work out what you need to know, or look at what you already know to identify how you could best augment that, either with data you collect or external datasets.

- Integrate geographic, power and relational mapping to strengthen strategy The sister disciplines of power and relationship mapping can be very effectively combined. For example, workplace organisers can map the geography of their workplaces in relationship to the individuals that work in each part of them, especially where their leaders are located, where they move, the relationships they hold and the ones they can build. It is worth considering how these other forms of mapping may complement geographic mapping.

Our thanks goes out to Natasha Adams for conducting this research and all of the interviewees for their time. You can download the full research paper here or read about it on Natasha’s blog.

If you would like to talk to us about this research, or anything related to mapping for movements, email us at hello@commonknowledge.coop.